SFAI GRADUATE LECTURE SERIES

Rudy Lemcke : The New World: Of Video Games and Museums

San Francisco Art Institute, July 16, 2018

1

2

“… man is an invention of recent date. And one perhaps nearing its end.

If those arrangements were to disappear as they appeared

if some event of which we can – at the moment – do no more than sense the possibility – without knowing either what its form will be or what it promises – were to cause them to crumble – as the ground of Classical thought did at the end of the eighteenth century – then one can certainly wager that man would be erased, like a face drawn in sand at the edge of the sea.”

Michel Foucault. Les Mots et les choses (The Order of Things, 1966)

3

I’m going to talk tonight about my recent work The New World. An installation that I made for the Kimball Educational Gallery artist’s residency at the de Young last Fall.

4

And also preview a new video game called, Cloud Forest – Annunciation, being installed at the Berkeley Arts Center this week and opening this Saturday.

5

Tonight, I hope to offer a different entry point into my art practice. A speculative narrative that prepares the way for the Homo Novum – the new mankind – that Foucault points to in The Order of things.

6

I’m also currently working on a trilogy of curatorial projects called, The Turning, Queerly that includes: From Self to #Selfie (2017), A History of Violence (2018), and Precarious Lives (2019). The project reconsiders the notion of the self as self-with-others; explores the scene of violence and trauma as trigger and turning point –

7

and proposes a rethinking of alliances and old models of political organizing that looks to reform the ideas of self and community.

8

I’m currently work on the 2019 show, Precarious Lives. Dinh Q. Le is one of the artists I’m thinking about including in the show. I’ve included this image as a visual reference.

9

The thesis that I am working through in my visual art, and curatorial and social projects involve existential questions: How do we live and find meaning when our world is collapsing, when everything that once defined us is in the state of rapid transformation? How do we understand the sites that house the symbolic and material richness of our past? How do we understand our lives in relation these spaces?

10

How do these ideas play themselves out in sites like this?

11

Some background notes:

I went to school at the University of Louvain in Belgium in the 70s. This is the Institute for Philosophy where I studied.

12

During the summers, I picked tobacco as a migrant worker in Ontario Canada to pay for my education.

13

These two places/experiences taught me how to think and feel about being in the world. But the contrast between the part of me that was a philosophy student and the other part of me that was living as an illegal farm worker each summer set up a type of cognitive dissonance – the mental state of holding 2 conflicting believe systems at the same time. It’s this tension between theory and the practice and politics of everyday life that became my struggle over the years.

Looking back on it with an expanded vocabulary, I wanted to queer philosophy as art and social practice.

14

(Slide With Word Geworfen)

Geworfen is a german term used by the philosopher Martin Heidegger that means “to be thrown.” He used the term to explain that we are thrown into an already existing world – that we are literally born into conditions beyond our control.

15

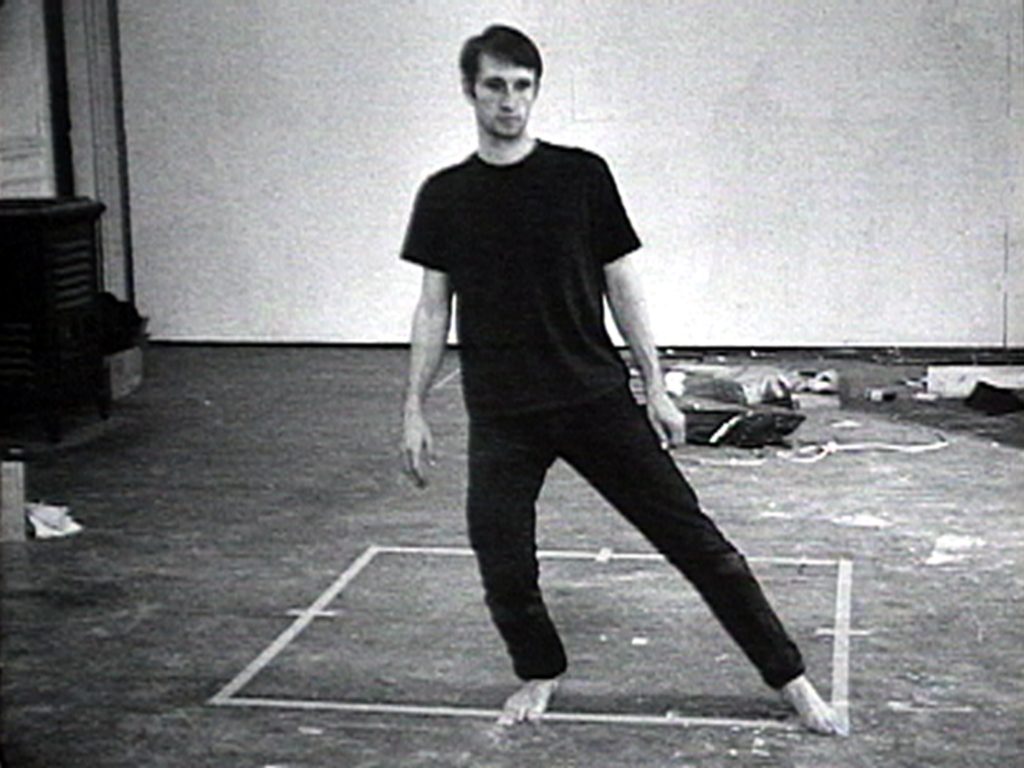

(Image: Bruce Nauman, Dance or Excercise on the Perimeter of a Square, 1965)

My geworfenheit my “throwness” was the culture and politics of the late 60s and 70s. In the art world – performance and body art was in ascendance.

16

(Image: Robert Smithson, Spiral Jetty, 1970)

Earthworks and LandArt were changing what was considered the site of art.

17

(Joseph Kosuth, One of Three Chairs, 1965)

And Conceptual Art set the stage for my thinking.

18

I was thrown into an existing philosophical and theoretical frame by my studies. I can clearly trace a line from the work of Michel Foucault and his important book, The Order of Things, to the work of John Cage, to experiments in performance installations, Political and Cultural Activism, my artwork about AIDS, Experimental Video, and most recently, Video Games and Curatorial Projects. All of these activities have folded back upon themselves in many ways over the years.

19

I want to say a little about Foucault because he was so influential in my thinking. Michel Foucault was part of a movement called Post-Structuralism. This was a movement that took hold in the late 60s and 70s and has resonance even how. The key takeaway from this movement for me was that it de-centered the idea of human subjectivity. That MAN in the cultural sense is not an essential being with preconditioned structures of knowledge. The Post-Structuralists theorized that we are a construction of our socio-political state, our cultural conditioning, genetic make-up, familial and economic status, and a complex array of systems of power; and that the self, our identity is constructed. It’s not to say it is arbitrary but not essentially fixed.

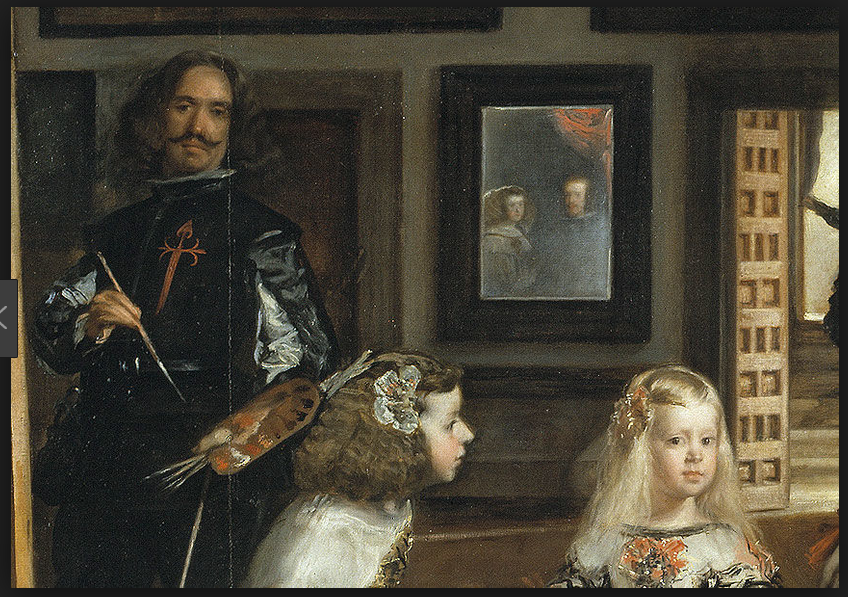

In the first chapter of The Order of Things, Foucault analyzes Valasquez’s Las Meninas (1656), The value of the work for Foucault lies in the fact that it introduces uncertainties in visual representation at a time when the image and paintings in general were looked upon as “windows onto the world.” Foucault finds that Las Meninas was a very early critique of the supposed power of representation to confirm an objective order visually.

20

Foucault’s theories address the relationship between power and knowledge, and how they are used as a form of social control through societal institutions. My interest in Foucault and Post-Structuralism was an interest in how language, culture, and politics form the conditions in which we as Humans are known.

So, from Foucault, comes this idea of exploring the fields of knowledge and power – the frames, the rules of the game within which we can know the world through language. My early work and actually the work I’m doing today, foregrounds the “un-fixed”, referential frames where the conditions of meaning are made possible.

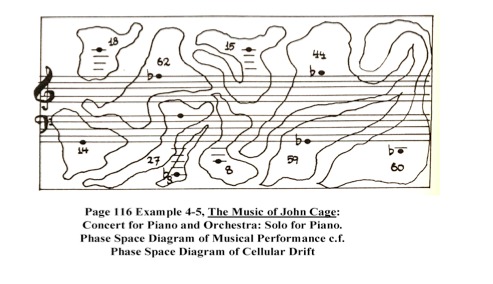

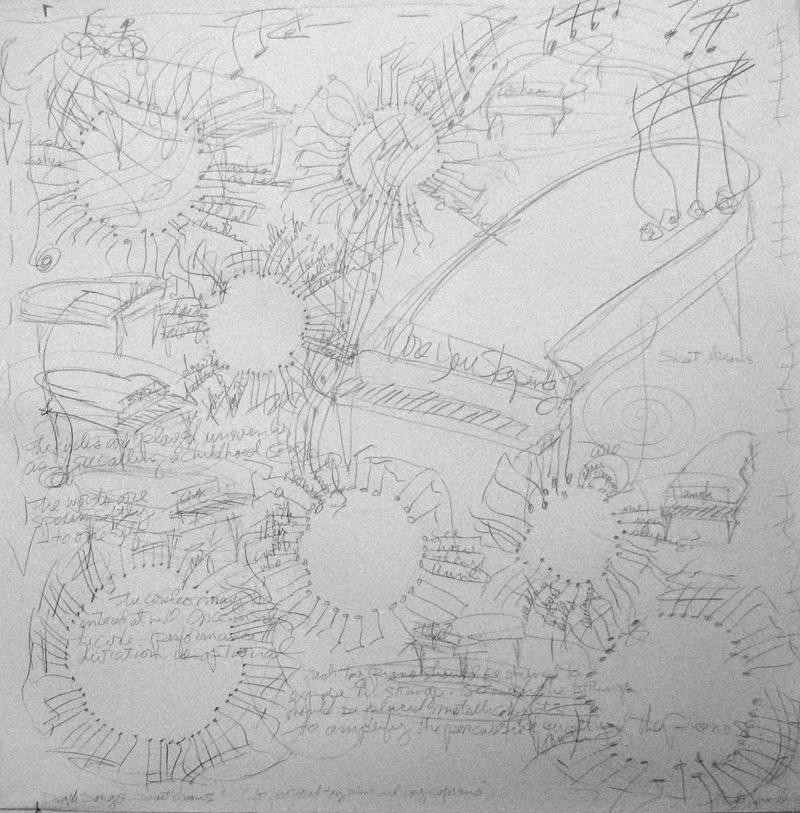

21

My other major influence was John Cage. It’s actually hard to categorize his work because it’s really a hybrid of conceptual art, life-art, performance art, and music. He was a student of Zen and was interested in the idea of chance, and of the random, ephemeral qualities of experience. In his most famous piece called 4’33” he gave a concert where he sat silently at the piano for 4 and a half minutes, putting the focus of the work on the audience and the experience of listening rather than on the playing of a piece by a master pianist. The sounds in the audience – the audience’s restless movement, breathing and occasional coughs – became the music. His musical notations (his scores) were brilliant works of art. They included opportunities for chance and free play to operate in the course of performing his music. Key to all of this was his performance notation, it was his scoring of these events that interested me as an artist.

22

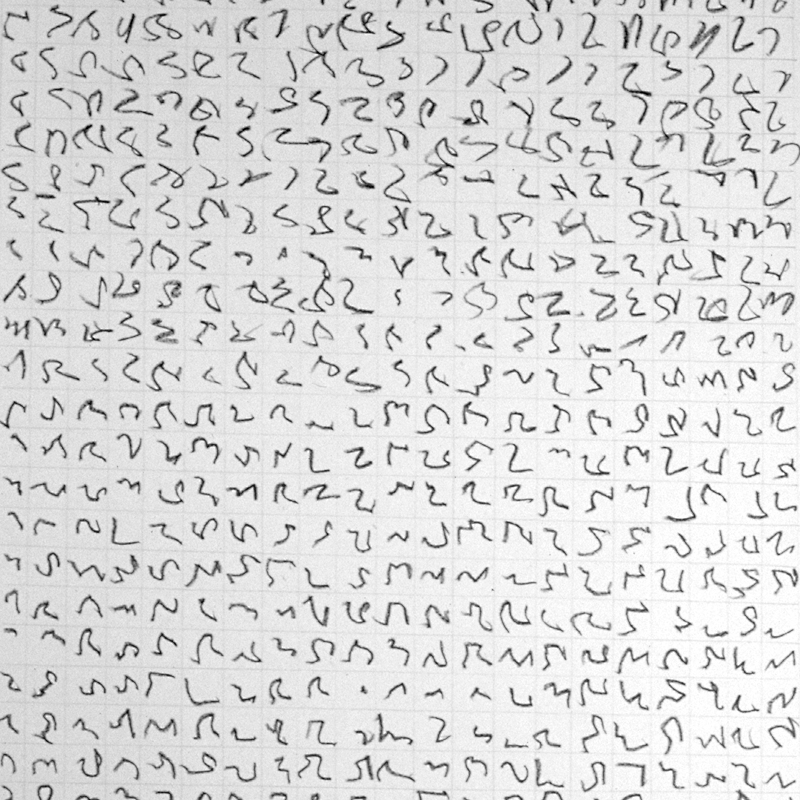

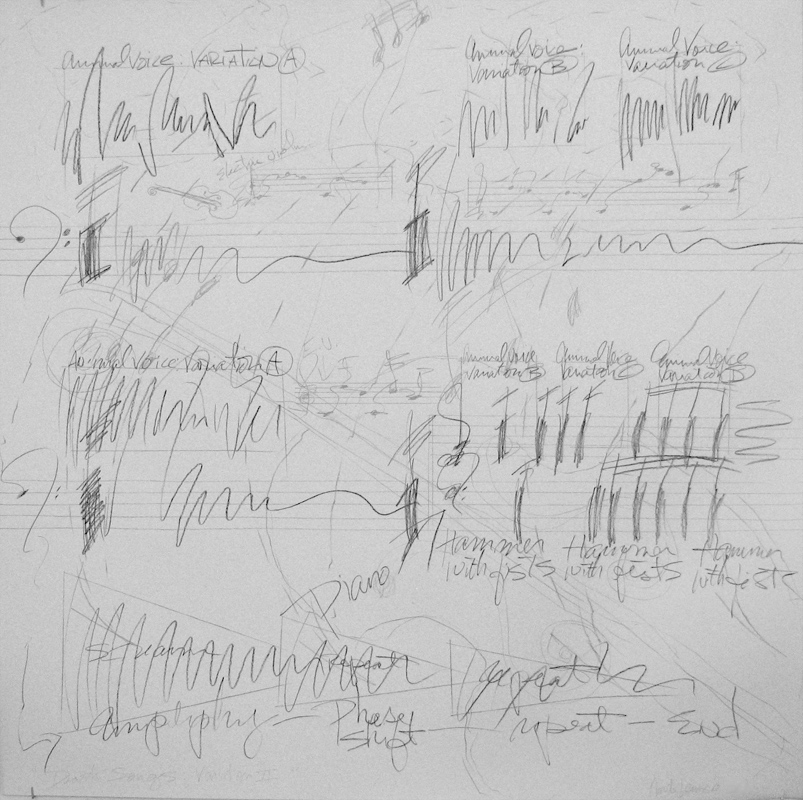

This is one of my early performance score 1977.

23

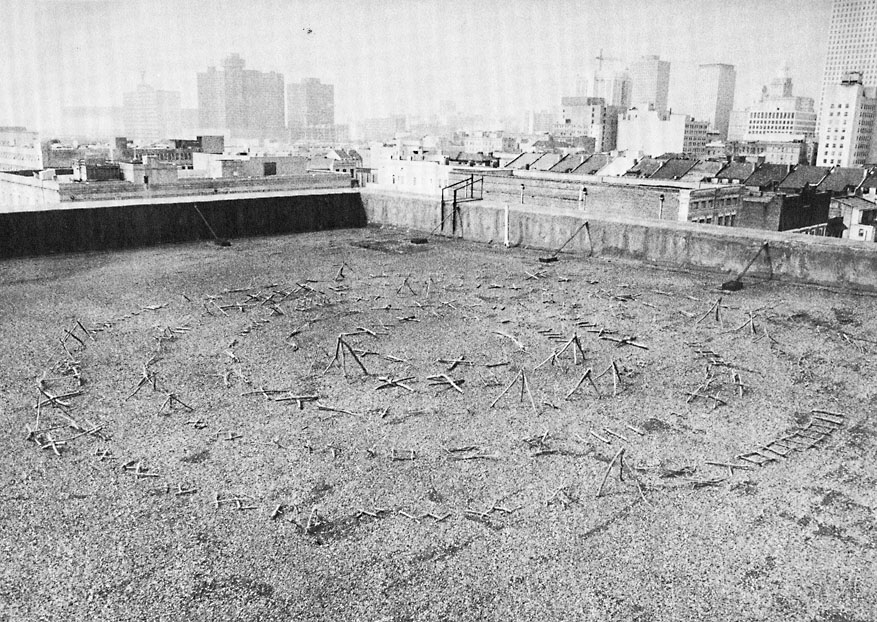

One of my performance installations from 1978 at the Contemporary Art Center in New Orleans.

24

This is the notation/drawing for this piece.

25

This is another performance installation at the Contemporary Arts Center in 1978. For these performance sculptures, I wrote performance notations and then laid the score out spatially usually with found organic materials like dirt or sticks. The scores directed the performer’s actions as the subject moves though the space.

26

This was a score for breathing from 1978. I loved using the rooftop, the basement and the garage area of the Contemporary Arts Center to explore the margins of the gallery space.

27

This was an installation I made for Southern Exposure Gallery in 1980. My first piece in San Francisco.

28

And this installation in 1981.

29

The scores were a set of rules; the conditions within which we can experience a work of art.

30

I didn’t intend for the viewer to actually perform the movements or actions described in the notations. It was always the idea of moving through a set of predetermined rules for performance that I was getting at in the artwork.

This same idea is what interests me in video games, I’m still exploring these conditions for making an experience possible. Only now I am using game space and writing the rules through creative coding.

31

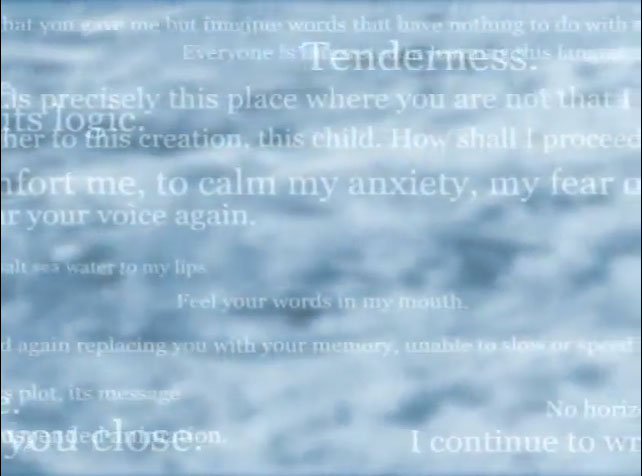

(Screen grab from Caress (after Roland Barthes), 2001)

This was my first attempt at video art. The text is partly taken from Roland Barthes’ book, A Lover’s Discourse. In the text, we are given fragments of ideas about love and loss. It is written in a way that draws the reader into the text. I queered it up a bit by adding lines about same sex desire. At some point in the reading we come to the awareness that we are the main character – the reader is the main character. I’m trying to get the viewer to be self aware of their complicity and self involvement in the creation of the experience of art.

32

33

This is another early piece called, The Uninvited (2003). It was originally created as an interactive non-linear Flash animation to be played on the computer. Each of the shadows were triggers that generated random lines from the underlying poem. I then reformatted the piece into a linear video projection a few years later. The video was projected onto a wall of a gallery space in a way that the viewer becomes one of the shadows. So the randomness that I built into the the Flash animation becomes a physical experience of being a part of the art work when presented as a video installation. This piece was included in the traveling exhibition Art, AIDS America curated by Jonathan D. Katz. It’s not specifically about AIDS. It’s more about abjection, that which lies outside the symbolic order.

34

The Uninvited (2003) from Rudy Lemcke on Vimeo.

35

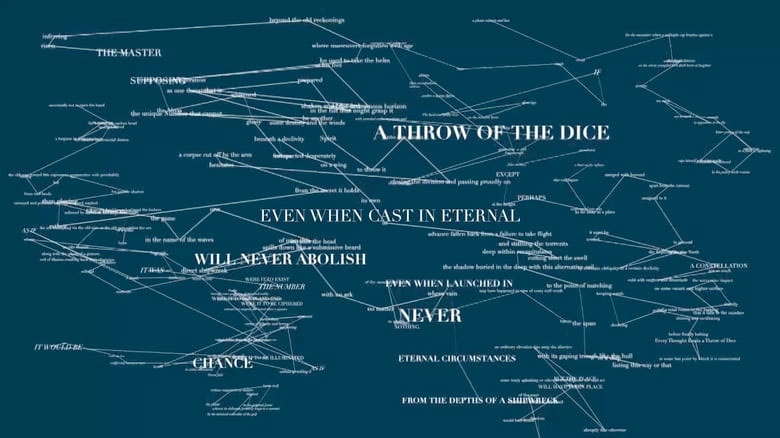

This is a more recent video from 2016 called Un Coup de Dés (after Mallarmé). Mallarmé’s poem was written in 1895. It talks about existence and the poetics of Chance. That we are thrown into a field of language that is the world and no matter what we do we are always at the mercy of a random throw of the dice.

36

Un Coup de Dés (Variation VII) after Mallarmé by Rudy Lemcke from Rudy Lemcke on Vimeo.

37

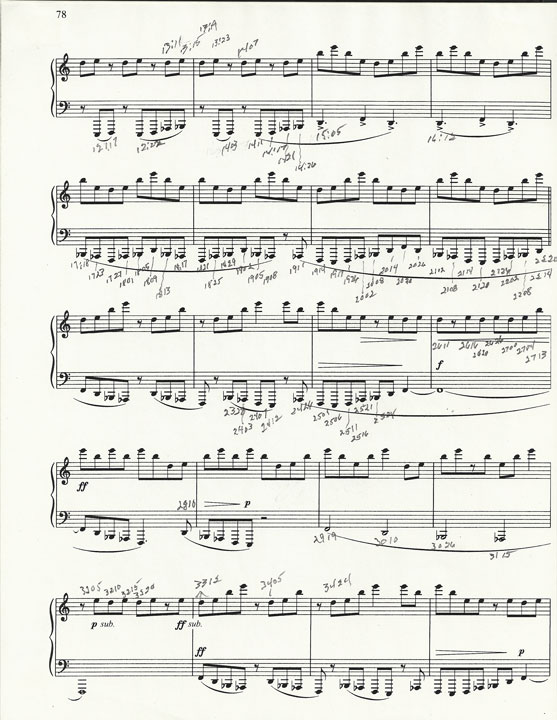

I just want to make one more detour before getting into game space. This time into the political sphere. During the 80s the AIDS epidemic exploded around the world and its epicenter was San Francisco. I worked exclusively on Art about AIDS for almost 10 years. In a 2007 I did a retrospective exhibition of my work about AIDS at LGBT Community Center and created a video called Where the Buffalo Roam as the center piece for the show. The video uses Cage’s Perilous Night piano solo as both the sound track and the editing guide.

38

The film I’m going to show has 2 parts. The first part is video footage I took at an ACT UP demonstration at Market Street and Castro, San Francisco in 1992. In the second part, when you see the hands playing the piano for the second time, the use of the Cage score and the editing becomes more pronounced.

39

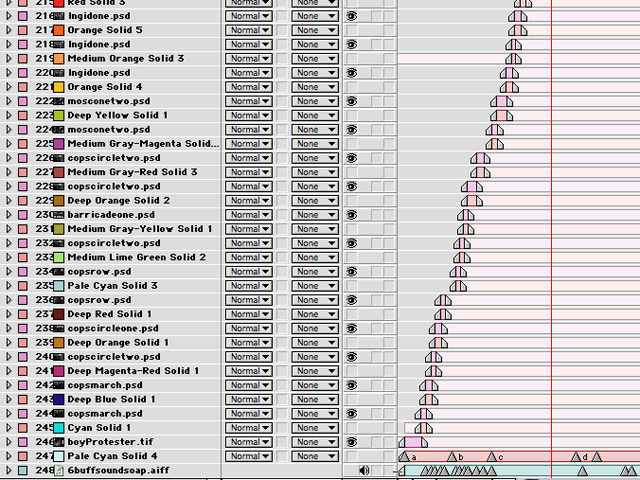

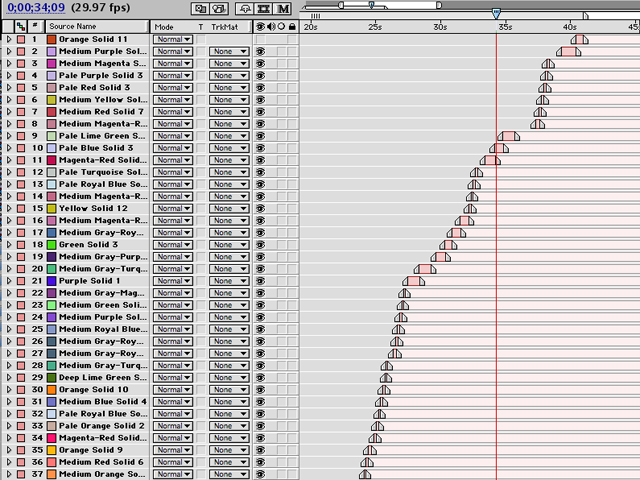

The musical notation of this piece was translated into an editing score in After Effects.

40

This was the user interface for After Effects in 2007.

41

42

It was a natural evolution for me to move from performance scores and musical notation to creative coding. This is the character controller script from my new game.

43

I’m going to fast forward to last fall and my residency at the de Young.

44

I proposed a project called The New World that included a video game that offered some new ways of thinking about the museum; and about memory and history and thinking about our place in time and space and new ways of thinking made available though technology.

45

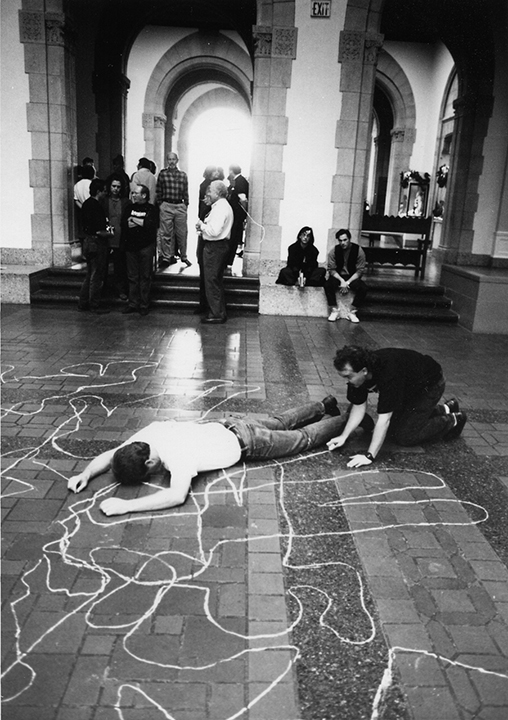

But the de Young had a haunted past for me. In 2002 I created a performance installation called Immemorial for A Day Without Art in the main entrance of the old museum. The performance was a die-in with the staff of the museum and the visitors that day.

I wanted to acknowledge the memory of this event in my new project.

46

As a part of the installation I made 100 purple hand sewn velvet pansies that stood in for the lives lost to AIDS and referenced my past work in the museum.

47

I wanted to explore how the idea of the “polytemporal” was working in the space of the museum. In music it means that a composition has multiple time streams and continuous tempo changes. I wanted to prompt many different understandings and experiences of temporality – like the idea of the relationship between now and then, fast and slow, old and new, before and after and how these ideas of temporality are changing in the digital world and creating new ideas about the way we think about time and space.

48

The installation contained 4 video loops like this one of me sewing the pansies and 2 interactive game spaces.

49

This is a clip from my iphone as you enter the space.

50

I moved the pansy configuration every day as the base form of the piece but also by changing the configuration I wanted to destabilize the experience by adding a randomness to the installation.

51

I wanted to acknowledge the trace of the exhibitions that occupied this space. And acknowledge that the museum has a memory reserve that can be accessed and played with.

52

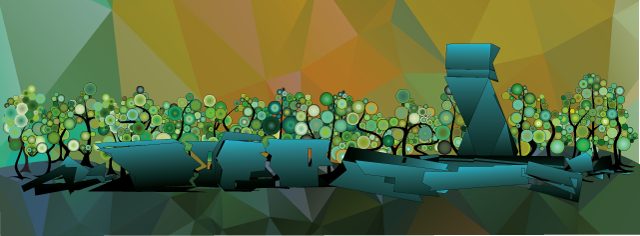

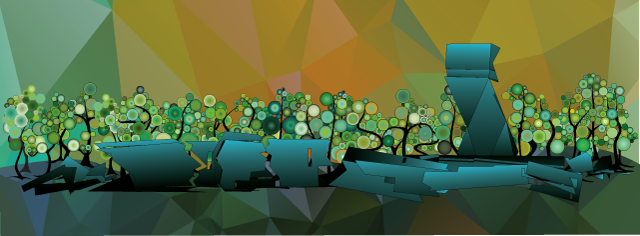

This part of the installation was the video game Pansy Farm. The game takes place in the future, of course, on the site of the collapsed museum.

The main character has to get through the obstacles and game enemies (a set of avatars of Modernist Sculptures. Many of the pieces were works in the collection of the Fine Arts Museums). The goal is to get to the Pansy Farm level.

53

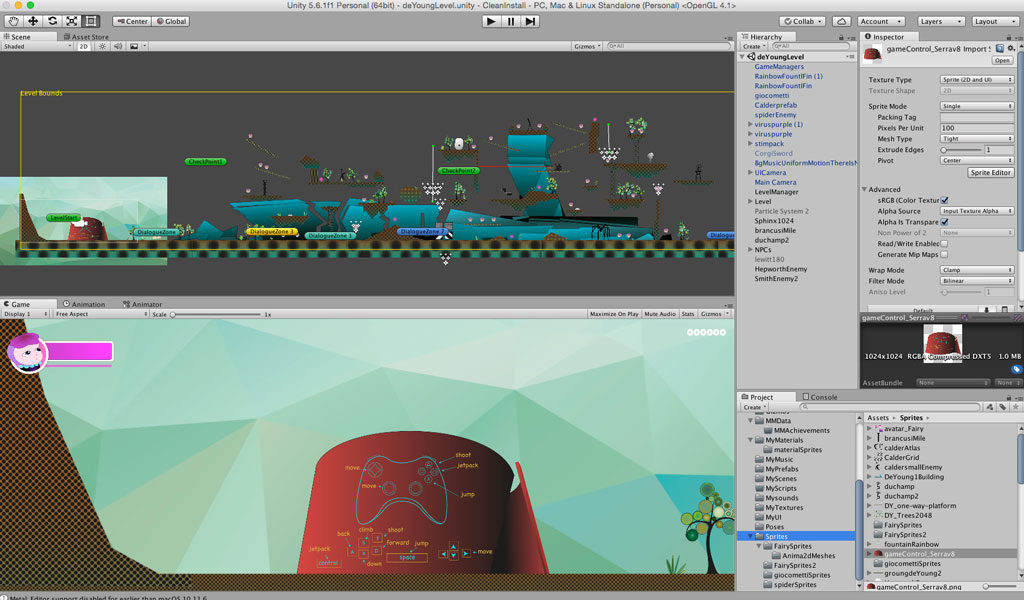

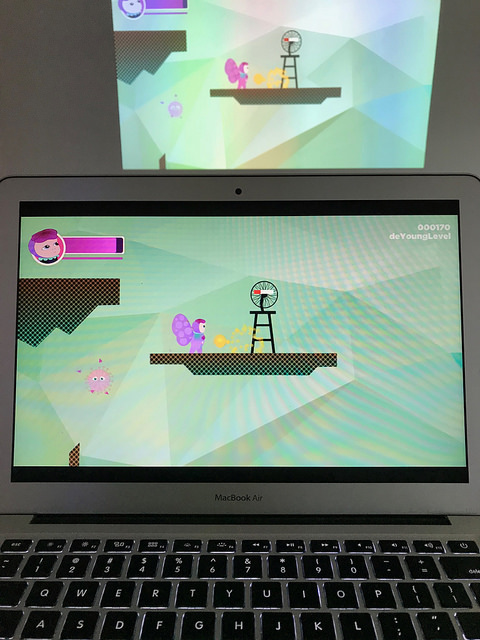

This is the interface for Unity software that I used to develop the game. I chose to make a simple retro platform game to teach myself how to use the software and learn how to code in C#.

54

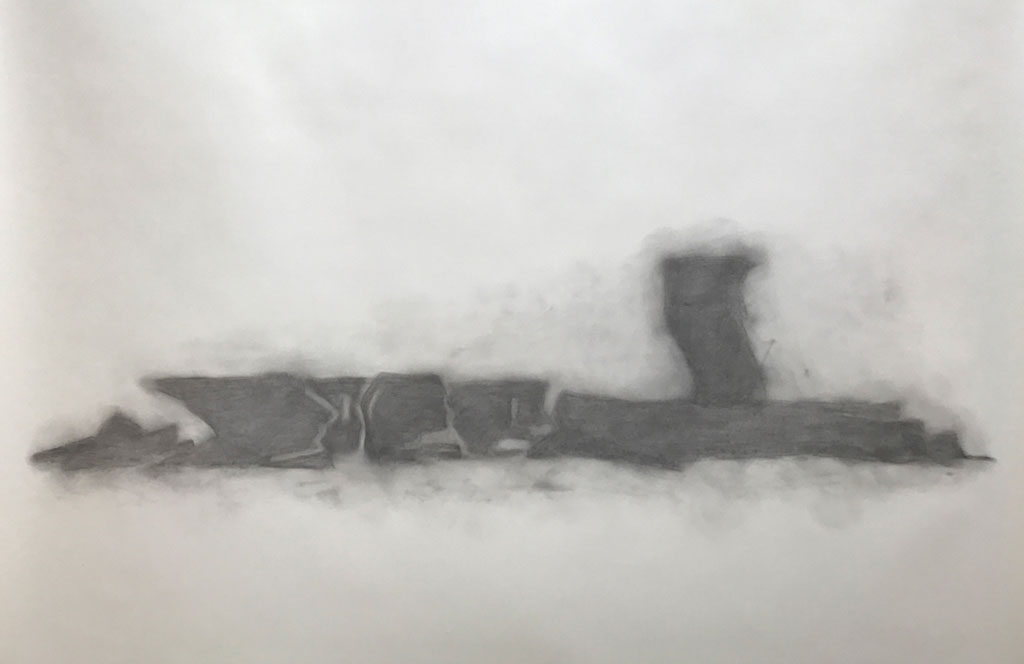

I’m going to run through a few slides to show you the process of game development because people are always curious about how a game is physically built. This was the original concept drawing I had for this game. The museum in ruins (this phrase is borrowed from Douglas Crimp).

55

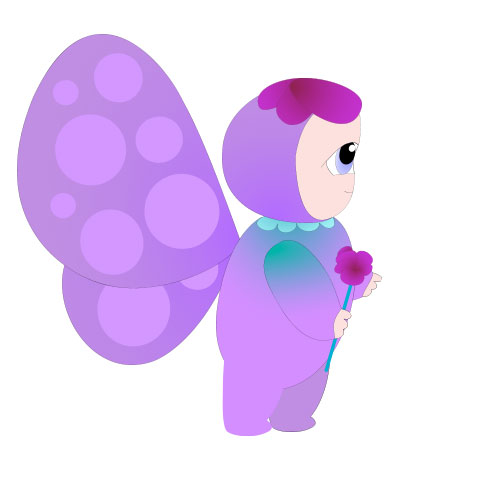

This is the Fairy protagonist.

56

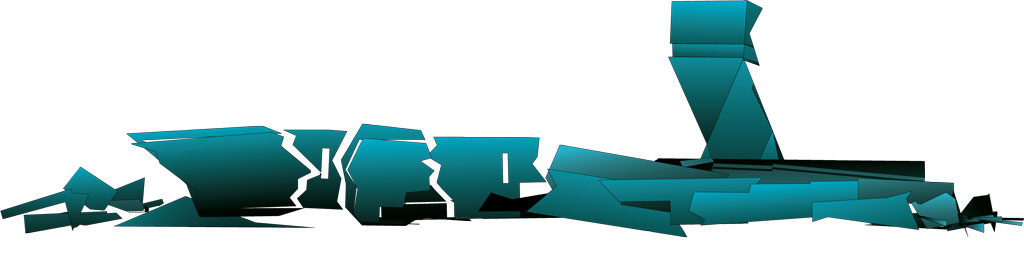

The design was then taken into illustrator and sliced to make it ready to be inserted into the game software.

57

The translation of the main character.

58

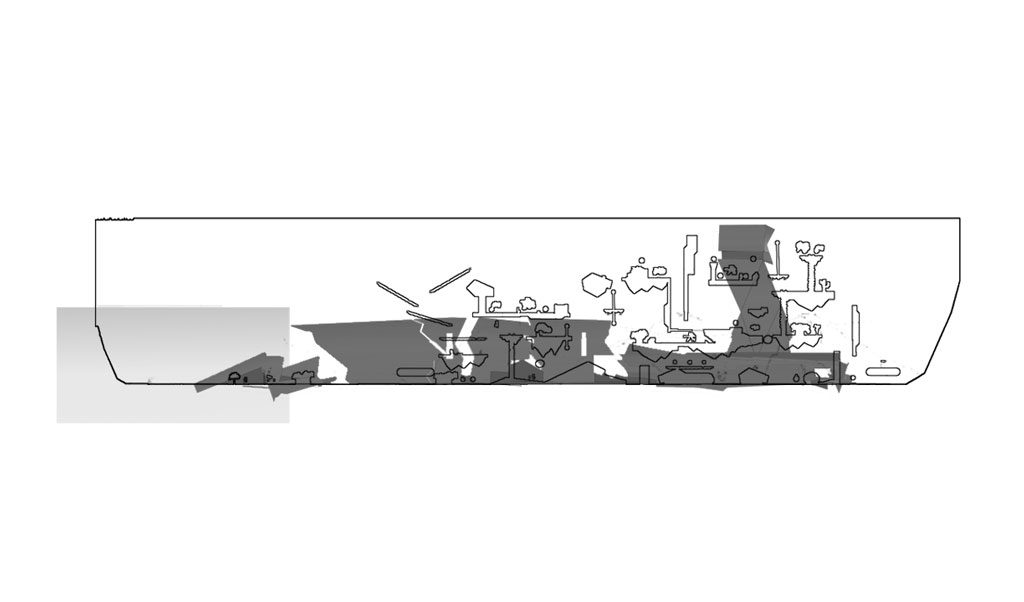

This is a study for the interaction design and game play.

59

And how it all comes together in the software interface.

60

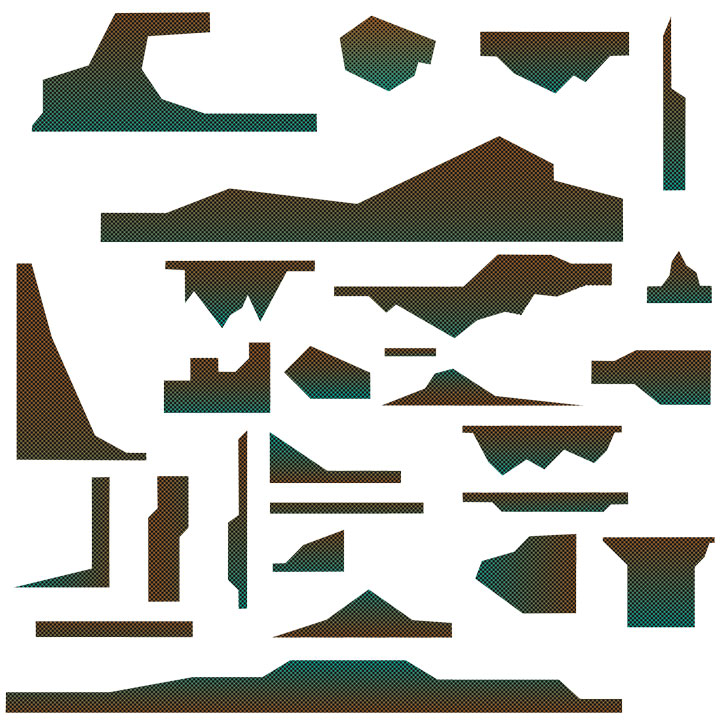

Platforms

61

Trees and small plants used in the game.

62

the character broken up for animation.

63

a rainbow fountain animation.

64

One of the enemy characters. A Henry Moore sculpture throws bombs at the fairy.

65

I used the Serra from SFMOMA at the beginning of the game to show the user how to work the game controller.

66

67

The game as seen on Iphone or iPad.

68

The game on my laptop – the fairy blowing up a famous Duchamp piece.

69

Pansy Farm Game Play from Rudy Lemcke on Vimeo.

70

This is level Two.

71

Across from the Pansy Farm Game was the interface of the Fine Arts Museum’s permanent collection – the data mine. I had the visitors create game characters and speculate about what new game levels could be developed. The idea of opening the collection and its rethinking of space, both real and virtual, was the point of this part of the installation. The Bird Characters in this level are trapped in cages and the main character needs to figure out how to free them. The birds are all wearing masks from the African and Oceanic collections.

72

The Pansy Farm is the Third and Final level.

73

These are prints of my studies for the Pansy Farm. They’re 36 x 36” each.

74

These are studies for other game worlds…other levels and spaces where the game might lead us.

I found that young people very easily understood what I was doing – how this all worked with its multiple dimensions, time travel, strange cultures existing together – and figuring out how to navigate through these worlds.

75

76

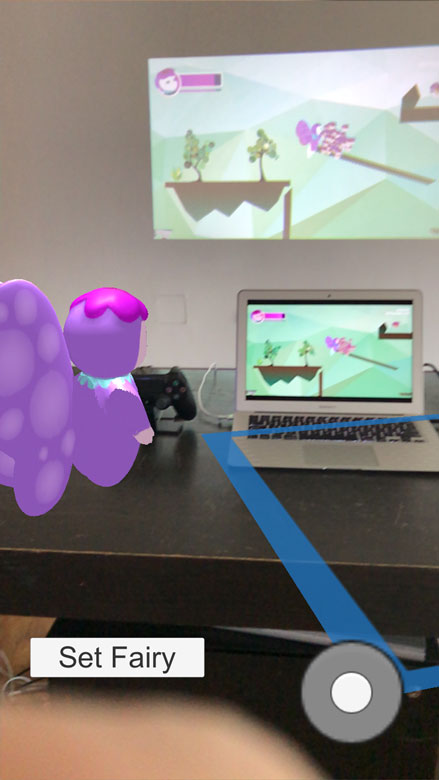

I added an Augmented Reality component for fun because Apple had just come out with it’s AR Developer Kit and I wanted to try it out. I’d already done a project in AR but I wanted to try out Apple’s software. So I made the little fairy character move around the space.

77

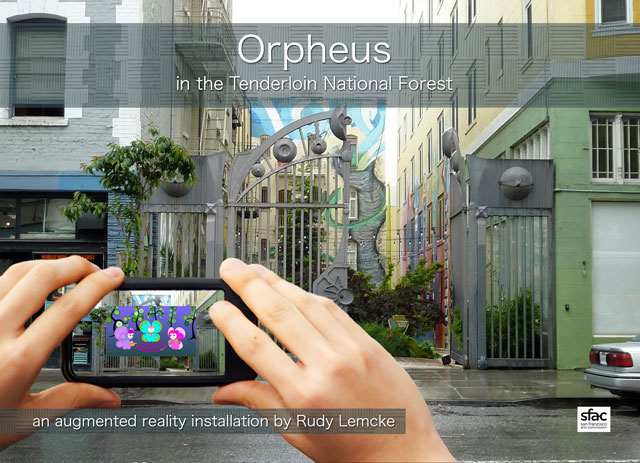

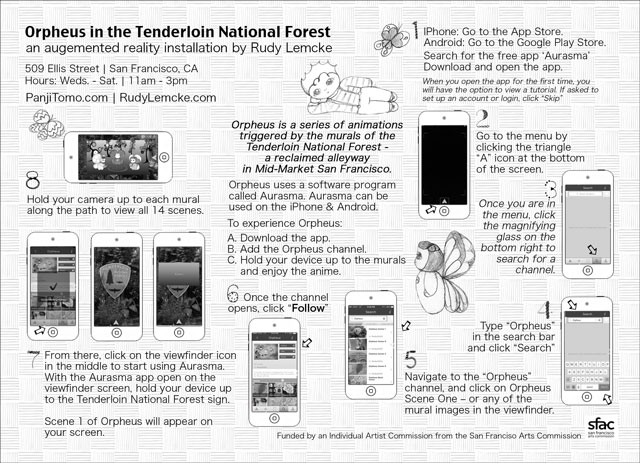

I originally came up with this whole fairy mythology in 2015 when I made an AR piece for the Tenderloin National Forest — an urban garden here in San Francisco in the middle of the Tenderloin. The animations that augmented the space were triggered by the murals that surround the perimeter of the park.

But there were many complicated issues around this piece. I originally came up with this whole fairy mythology in 2015 when I made an AR piece for the Tenderloin National Forest — an urban garden here in San Francisco in the middle of the Tenderloin. The animations that augmented the space were triggered by the murals that surround the perimeter of the park.

But there were many complicated issues around this piece.

78

The technology was new, it involved many steps for the viewer to get it working, the site was nearly always closed to the public, so I didn’t really think of it as successful.

79

These were the instructions – needless to say, not too many people actually saw the piece.

But I had spent a year on the animations and didn’t want all that work to go to waste.

80

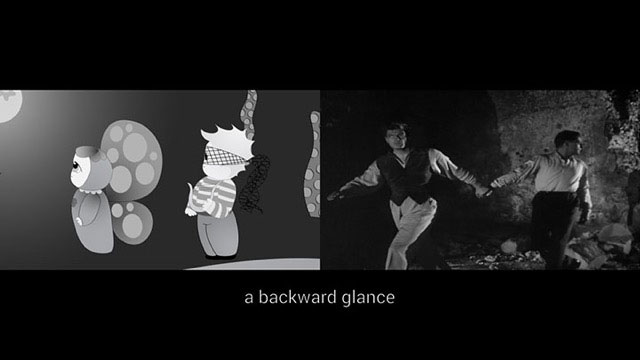

So I reformatted the AR animations into two new projects: This one is (Orpheus) The Poetics of Finitude that uses Cocteau’s 1950s film to deconstruct the myth of Orpheus.

81

A few screen grabs.

82

83

Fey Ontology | 2016 from Rudy Lemcke on Vimeo.

and another piece called Fey Ontology where I showed all of the 48 scenes of the animation simultaneously. Both of these videos became a part of my New World installation.

84

With all of these layers I wanted to show the museum as a game within a game – the collection as an open source – and allow visitors to co-create its narrative.

My work in the last few years raises the question of the self in the digital age and the places we build.

85

Just a few months before the de Young work, I curated the exhibition titled, from Self to #Selfie at SOMArts Cultural Center.

From Self to #Selfie examined queer self-representation in the light of the revolutionary transformation of culture that is taking place through digital technology.

The exhibition asks: Where do I “exist” in the network of information that is instantly made available through a touch of our smart-phone’s interface? Where do I “exist” in the multiplicity of screen instances, recursively generated by the image I call #selfie?

The exhibition offered eight video explorations of the body mediated through the digital screen. The intimate acts of performance encoded by these videos with their gestures of attention and affection together manifested a complex queer cultural ecosystem – a queer public commons within which the self becomes re-presented and re-imagined within a referential field of other screen selves presented in the exhibition.

My thesis for the show was that the networked self exists in a new relational order as self with others with its hashtag self – the #selfie as ecstatic-self.

86

Right after my residency, I started curating the History of Violence show. It represents the second part of The Turning, Queerly trilogy. Here’s a short excerpt from the introduction.

Violence is perpetrated through politics, economics, and culture – and made real through human interaction. Poverty, social injustice, state sponsored brutality, racism, sexism, homophobia, intolerance, and oppression are examples of its instrumentality. All are symptomatic of systemic violence manifesting itself in our daily experience of the world.

The exhibition asks: Is resistance possible?

The idea of resistance itself implies a point outside of the system from which to act and critique this violence. But what if there is no outside? If so, could there instead be a place of turning from within that might trigger the emergence of a new becoming, queerly? What would this turning look like? What would it feel like?

For each of the artists in the show – there was a sense of this turning – of trauma and violence into reparation and agency.

Again the question of subjectivity and agency become the struggle. Right after my residency, I started curating the History of Violence show. It represents the second part of The Turning, Queerly trilogy. Here’s a short excerpt from the introduction.

Violence is perpetrated through politics, economics, and culture – and made real through human interaction. Poverty, social injustice, state sponsored brutality, racism, sexism, homophobia, intolerance, and oppression are examples of its instrumentality. All are symptomatic of systemic violence manifesting itself in our daily experience of the world.

The exhibition asks: Is resistance possible?

The idea of resistance itself implies a point outside of the system from which to act and critique this violence. But what if there is no outside? If so, could there instead be a place of turning from within that might trigger the emergence of a new becoming, queerly? What would this turning look like? What would it feel like?

For each of the artists in the show – there was a sense of this turning – of trauma and violence into reparation and agency.

Again the question of subjectivity and agency become the struggle.

87

I was reading a lot of Hanna Arendt at this time and this quotation stayed with me.

The miracle that saves the world, the realm of human affairs, from its normal, “natural” ruin is ultimately the fact of natality, in which the faculty of action is ontologically rooted. It is, in other words, the birth of new [people] and the new beginning, the action they are capable of by virtue of being born. Only the full experience of this capacity can bestow upon human affairs faith and hope. ~Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition.

88

I was working simultaneously on A History of Violence and a new game called, Cloud Forest – Annunciation. It was a delayed, unseen artistic contribution to the exhibition – a different way of working through this idea of violence – outside of the physical frame of the exhibition but inside of its conceptual field.

The metaphor of the “cloud” references both the ephemeral natural phenomena of clouds and also references “data clouds” that hold digital information about representations of the world as standing reserve – as data that have the potential to take physical form through technological manipulation and just as quickly disappear.

89

Cloud Forest’s visual design is based on the painting, The Hunters in the Snow by Bruegel the Elder (1565). The painting depicts a group of weary hunters returning empty handed to a snow engulfed, idyllic village scene.

90

The Bruegel painting reference also points to the painting’s appearance in Tarkovsky’s science fiction film Solaris as a visual metaphor for a failed journey; a journey that takes its characters to a mysterious planet that makes real the fantasies and dreams of its visitors. These fantasies carry with them an unforeseen violence that is hidden beneath the desires of its explorers.

91

The failed journey is the collapse of meaning, the existential crisis and question, who am I?

92

Cloud Forest Video Game Play from Rudy Lemcke on Vimeo.

I’m going to end with a short clip of game play from Cloud Forest. The game is literally an open field, there is no so shooting, no winning or losing – it is an anticipation – a walkabout.