From Self to #Selfie

From Self to #Selfie includes three interconnected components: the main gallery features eight large-scale video projections by artists Kia LaBeija, Awilda Rodriguez Lora, Cassils, M. Lamar, A.L. Steiner, boychild, Tina Takemoto, and Evan Ifekoya; four video monitors suspended in the corners of the exhibition space loop 100 photo-selfies solicited from Bay Area LGBTQ artists; and in an annex gallery a video installation created by E.G. Crichton includes self-portraits gathered from eight international LGBTQ historical archives.

The exhibition does not attempt to position itself within a linear history of LGBTQ identity represented through the visual art of self-portraiture. Rather, it reframes the idea of looking at identity using the exhibition as a fluid system within which a queer self might be known. The exhibition is not negating the importance of historical narratives of same-sex desire in visual art or the importance of accurately articulating the lives and loves of the artists that are central to a richer understanding of our world. It builds upon work that has greatly advanced the cause of social justice and advanced the field of art history.

It is precisely because of this previous work and focus that we become open to new ways of entering the space of queer subjectivity. Just as the words homosexual, gay, lesbian/gay, LGB, LGBT, queer, gender queer, non-binary, or non-conforming become more useful or less useful over the years, we continue to find more or less useful ways of articulating ourselves in the visual language of the day.

The exhibition turns to deconstructive curatorial tactics to formulate a strategy for addressing what is the complex and perhaps impossible task of articulating a theory of queer subjectivity in self-portraiture. Curatorial practice, video art, performance, and new media are often confronted with the problem of mediation and the entanglements of fixing a simple tag on a process of dynamic animation. The complication that is always running alongside this process is a constant struggle with the desire for clarity, visibility, and recognition while often becoming opaque, insular, and ambiguous in its form of presentation. The exhibition explores a middle way of addressing this conundrum by reframing the approach to thinking about queer subjects.

- Ground

The motivation for the exhibition reaches back to a particular lineage of Bay Area LGBTQ self-portraiture that began in 1998 with the San Francisco National Queer Arts Festival’s first visual arts exhibition, FACE: Queerness in Self Portraiture.

As the introduction to the inaugural exhibition states: “We wanted a place to start; to begin a serious discourse on queer culture; a beginning that was not an absolute ideological position but a place that would be continually open to itself and its re-creation; a place that celebrated difference as its mode of being and justice as its practice. We wanted to present ourselves not as an abstraction (a theoretical category, a political identity group or an economic brand) but as an array of unique individuals who share this ‘queerness’. We gathered these artists together in hope of creating this place, this center. We decided to start with introductions … We decided to call this first gesture, FACE.”— (Lemcke 1998, p. 12).

- Figure

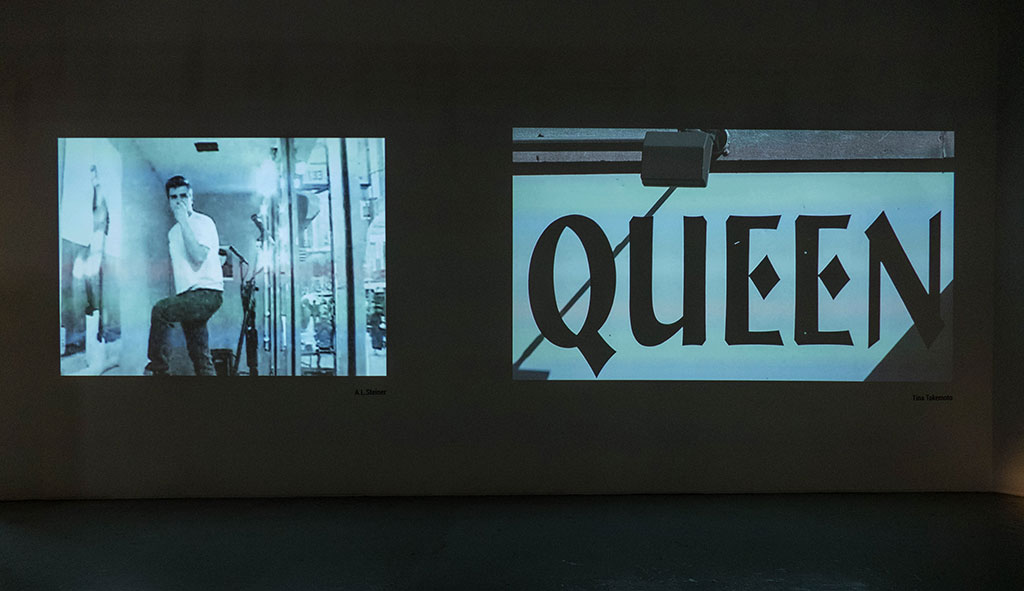

Twenty years after this first exhibition and occupying the same physical gallery space at SOMArts Cultural Center, From Self to #Selfie (Figure 1) revisits this theme of self-portraiture to think about queer self-representation in the light of the revolutionary transformation of culture that is taking place through digital technology.

In the phrase from above, “We wanted to present ourselves … as an array of unique individuals who share this ‘queerness’” (Lemcke 1998, p. 12); it is perhaps the word “share” that becomes the operative term in the figure to ground relationship between self-portraiture and self. It signals a bond between self and others that precedes and goes beyond the identity of the self.

Figure 1. From Self to #Selfie. Installation View. Exhibition at SOMArts Cultural Center, San Francisco, CA. 3–30 June 2017, curated by Rudy Lemcke Shown left to right: M. Lamar, boychild, Cassils, Evan Ifekoya. Photo by Rudy Lemcke.

For those of us involved with the first FACE exhibition, the transformation of queer culture coupled with the availability and accessibility of new technologies has been dramatic. But the new access, speed, and interconnectivity that these new technologies afford the social justice movement also come at a price. An oppressive meta-structure of surveillance and control lies in the background as its authoritarian shadow. Noteworthy amidst this turbulent rupture of political and cultural identity brought about by social change and new technology is a curious obsession with the act of self-expression and self-portraiture encapsulated by the term #Selfie. Perhaps it is an existential question being raised when we ask such questions as: Where am I in the network of information that is instantly made available through a touch of our smart-phone’s interface? Where do I belong in the multiplicity of screen instances, recursively generated, broadcast, consumed and disposed of with the careless abandon of a “delete” keystroke? What is this #Selfie? What smiles back at me as I caress my smart phone?

The curatorial project hopes to understand how queerness operates in these questions of #Selfieness. The exhibition features nine explorations that are performed using the medium of large-scale digital video projection. As individual videos, the works demonstrate the dynamic materiality that speaks to ongoing conversations about gender as mutable and fluid constructs. Through multiple lenses, they perform identity as a liberation that reaches out beyond the confines of form.

Presented in continuous loop cycles, with only darkness as separation or barriers between them, the intimate acts of performance encoded in these videos with their gestures of attention and affection become unglued and manifest together as an immersive space. A queer public commons is created in which the self becomes re-presented and re-imagined in relation to a referential field of other screen selves. The installation makes it impossible to view one individual screen in isolation and presents these unique, idiosyncratic works within an exhibition as experiential field.

The exhibition offers a queer place that is physically located as a communal self-affirming space of desire and identification marked with queer signification and potentialities. In place of singular expressions of an arguably longed for “authentic” LGBTQ subject, one encounters “queerness” at work in this exhibition through the representations of a dynamic intentional self, embedded in a web of private and public, familiar, and unconventional relationships and systems of meanings through which it is articulated, reproduced, and projected.

It is the hyper-dynamic function of figure to ground and its reversal endlessly unfolding in this space that holds the idea of #Selfie that we are exploring in the exhibition.

Figure 2. Rudy Lemcke, 100 Selfies, four channel video, loops (detail), 2017. Presented at the From Self to #Selfie exhibition, SOMARTS Gallery, San Francisco, CA, 3- 30 June 2017, Curated by Rudy Lemcke. Source: Author photo.

Buttressing the corners of the gallery space are four video monitors that continuously loop 100 photographic images of Bay Area LGBTQ artists (Figure 2). The circulation of these photo-selves randomly generates an extended field with each digital portrait acting as a node that expands beyond the horizon of the visible. They are avatars of a new sociality. They are multivalent agents acting as both signified and signifier, message and signal, performance and audience. These #Selfies embody in their singular presence the signification of their networked ontology, and with this, a potent complexity attuned to the show’s video work.

The artists in this array of #Selfies represent artistic practices that go beyond their own idiosyncratic work and extend to communities of artist organizations and eccentric circles of support within which they are key participants and organizers. Some examples are Sean Dorsey of Sean Dorsey Dance, Shawna Virago of San Francisco Trans Film Festival, Debra Walker of the San Francisco Arts Commission, Pam Peniston of Queer Cultural Center, Favianna Rodriquez of Culture Strike, and Katie Gilmartin of the Queer Ancestors Project, to name a few. Their presence anchors the “work” of the exhibition within an extended queer community.

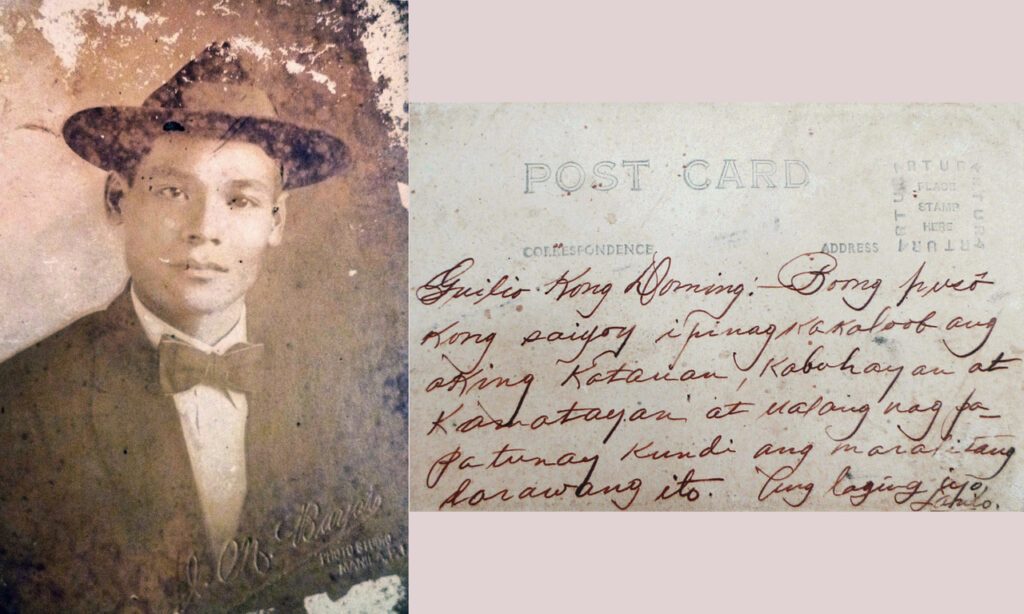

Figure 3. E.G. Crichton, RETRIEVAL: Six Portraits, 2017, digital video, 48:12 min. Photograph courtesy the artist, used with permission.

My beloved Doming,

I wholeheartedly offer you my body, life and death and nothing proves this more than this humble photograph.

Yours always,

Lauro

In an adjacent but linked gallery the video installation by E.G. Crichton, RETRIEVAL: Six Portraits, projects an international array of queer portraiture, drawn from historical circles of queer affiliations whose archives are now accessible because of the global movement of information and knowledge made available through technology. The scope of the project attests to the range and reach of this queer network.

Each portrait is a montage of photographs, letters, news accounts, and ephemera, thoughtfully assembled by Crichton. The post card above (Figure 3) was found in a flea market in Quezon City by the owners/archivists of Adarna Food and Culture, Philippines. Knowledge of its sender is suspended in a field of meaning held by the archive as “object” and simultaneously opened for us as “desiring subject” by Crichton’s video within the space and time of the exhibition.

The video portraits of RETRIEVAL: Six Portraits create a delicate bridge between analog and digital, private and public, local and global, and reveal a tension between our idea of the temporal past and the ever-presentness of the digital now.

Figure 4. Kia LaBeija, Dove, digital video, 4:51 min, directed by Jacob Krupnick, 2016. Photograph courtesy the artist, used with permission.

As its generative kernel, From Self to #Selfie affords us a vision of the rich potential to explore/refuse/resist/parody existing gender paradigms and to open the possibilities for “queer” identities as they are embodied in these new forms of queer sociality, affinity, and agency as they queerly emerge in a relational field of meaning on the screens of our networked world.

The exhibition is meant to demonstrate by immersion the performative space of self as agent in a network of provisional queer meanings that are grounded in the past (RETRIEVAL: Six Portraits), responsive to the present (100 #Selfies), and contemporaneously fixed and un-tethered to local and global spaces as networked selves co-existing in this new relational order as ecstatic-self, as #Selfie.

- Eight Screen Selves

It is hard to pinpoint exactly where the chronological process of selecting the artists for the exhibition starts, but Tina Takemoto’s film is certainly the best place to begin this narrative because it most succinctly introduces the complex dynamics of representation at work in the exhibition. The work has a particular resonance for me because of an on-going conversation I have enjoyed with the artist over the years about identity, history and memory.

Figure 5. Tina Takemoto, Semiotics of Sab, digital video, 5:35 minutes, 2016. Photograph courtesy the artist, used with permission.

3.1. Tina Takemoto, Semiotics of Sab

In Semiotics of Sab (Figure 5) we are presented with a portrait of film actor Sab Shimono in three sequence arcs. The first sequence presents a list of every character played by Shimono that quickly flashes on the screen in alphabetical order. The second sequence uses the structure of alphabet to present still and moving images of places, events, and names that resonate with Shimono’s life, for example, images of W 27th Street where he studied acting, the Other Side gay bar he frequented, and Amache concentration camp where his family was imprisoned during World War II. As the film introduces this new organizational pattern of images, a voice over from Shimono’s 1993 film Suture begins: “How is it that we know who we are? We might wake up in the night and wonder where we are. We may have forgotten where the window or the door or the bathroom is…But we never wonder who we are.” (Shimono 1993)

In Suture Shimono plays the role of a psychiatrist trying to help a man, who has been in an accident and suffers from amnesia, regain his memory. We begin to see Takemoto’s experimental play of semiotic order emerge in the film’s narrative structure that points to the nature of memory and identity. The repetition of the alphabetical sequencing using a different set of trigger images disrupts any attempt to fix an imposed order on a seemingly private and unknowable association of signification. Once again we hear the voice of the psychiatrist as he hypnotically swings a pocket watch, suspending time and consciousness in order to access repressed memories of a trauma that he believes are the key to integrating his patient’s lost self. “Let me take you back to a beginning, to a time before identity becomes confused.” The final section initiates a countdown from 10 using clips of Shimono’s various Asian and Asian American film roles that reach a terminal point in the death of his character in the simple clothes of a Japanese worker lying prostrate amidst rocks and turning waves of an indistinct shoreline.

The film’s style and technique looks back to a lineage of experimental filmmakers of the 1970s that sought to establish a new language of film following the example of linguistic structuralism. In breaking with the narrative structure of traditional film and imposing alternative systems of signification, these filmmakers ushered in a new era of radical experimentation that questioned the foundation of film aesthetics and its underlying theory of representation. Building on this experimental lineage, Takemoto introduces an expanded horizon of post-colonial thought that moves the question of identity and subjectivity to a deeper and a more profoundly beautiful experience.

The ostensible subject of the film, Sab Shimono, is held within a hall of mirrors that is the semiotic play of signifiers represented by Shimono’s screen personae. But just as the meta-subject of Velázquez’s famous painting Las Meninas (1656, Museo Del Prado) is held in the mirror reflection of the royal sovereign and holds the painting’s order of signification, so Takemoto’s film reflects the dynamics of race and identity that also frames the artist herself as subject.[1]

Figure 6. boychild, DLIHCYOB, digital video, 4:33 minutes, directed by Mitch Moore, 2012. Photograph courtesy the artist, used with permission.

3.2. boychild, DLIHCYOB—directed by Mitch Moore

The first experience I had with boychild’s performance art was in SOMArts Gallery a year before the #Selfie show. It is almost impossible to articulate boychild’s art-as-event—performance art that is truly meant to be an experience, and we are often left in silence when struggling for words.

Ironically perhaps, the most seemingly portrait-like of the projections in the exhibition is DLIHCYOB, a video of boychild, directed by Mitch Moore. But this portrait-like form belies its complexity. The video shows a close up of the artist’s shoulders and head in reverse color mode (Figure 6). An electronic sound track mirrors the slow and subtle butoh like movements of the artist. Is this an expression of “bliss”—a word that is tattooed on the artist’s neck? Nothing is said in the performance; its queerness seems to flow from the non-narrative nothingness of its time(less) gestures. One thinks of Cage’s 4’33” performance of silence when experiencing boychild’s video within the visual field of the #Selfie exhibition[2]. Cage’s silent, motionless piano performance was meant to fill the space of the auditorium with the ephemeral “music” of the listeners’ presence, shifting our attention away from the performer to our own subjective experience of listening. Similarly, boychild’s hypnotic performance in this relational space invites us out of, or by way of, a notion of the “self” and into a space where transformation and movement lead to new possibilities of world building often associated with queerness and queer survival. The “self”, as boychild illuminated in a recent email conversation, can be used as a tool to reveal the ubiquitous wholeness of being—dissolving difference. This idea shimmers amidst the light of the other screens’ selves.

Figure 7. A.L. Steiner, Swift Path To Glory, 2003–2007, digital video, TRT 9:44, 2003/2007. Photograph courtesy the artist, used with permission.

3.3. A.L. Steiner—Swift Path to Glory

My first encounter with A.L. Steiner’s work was in 2010 at the Roxie Theater in San Francisco at a screening of the video Community Action Center by Steiner and A.K. Burns. The film was part of Frameline’s International LGBTQ Film Festival and had a lively Q and A after the screening. When putting the #Selfie show together I went to Steiner’s website and quickly realized that all of the video work would be perfect for the show, but I chose Swift Path to Glory.

The multilayered Swift Path to Glory is shot in a storefront window—a space inherently construed as both public and private. It uses untrained actors to recreate the dramatic familial scene of a young James Dean in Rebel without a Cause (1955) as he pleads for acceptance.[3] The unidentified actors in the film emotionally charge their portrayal of the youth’s crisis through seemingly endless readings and failed attempts to be understood. Its LGBTQ audiences easily understand the scene as a young queer boy’s angst and recognition of the gender ambiguity of the filmmaker as James Dean photo in the background of the storefront movie set—a theory queen alert is triggered (Figure 7). To the uninitiated the scene can just as easily be thought of as so much cultural debris littering the congested urban street where it was filmed—its camp value, its queerness, arising and falling in the eye of the beholder.

In a 2012 conversation between Anthea Black and A.L. Steiner, Steiner speaks about identity:

“Space between the process and the product doesn’t end; it is similar to how we’ve talked about feminist history. There isn’t a conclusion, where now it’s this and we have to fight for it to be recognized as a certain thing. The idea of queer identity is that you’re not fighting to have to be ‘something’; you’re fighting to not have to be something. Rights and liberties and civil rights really rest on the idea of someone deciding that you’re valid enough, and they give you something. Then you’re complete. For me, philosophically, that is a fallacy.” (Black 2019)

While Swift Path to Glory humorously celebrates the complex performative aspect of gender, it is this idea of liberation as process that drives the work and is the powerful message of A.L. Steiner.

Figure 8. Cassils, video document of performance Hard Times, Photo by Luke Gilford, 2013. Used with permission.

3.4. Cassils—Hard Times

Cassils’s Hard Times (2010) is a hyper-articulation of the objectified self. It is a critique of gender constructions and our notions of beauty. It takes place in the world of professional bodybuilding where intense training and discipline are required to shape the body into a flawless reflection of the Greek ideal of human form. Cassils’s performance is a six-minute series of poses that are meant to glorify the body’s perfection. The performance takes place on scaffolding, surrounded by theatrical lights and the regalia of high drama. Wearing a gruesome prosthetic mask (Figure 8) meant to represent the Greek profit Tiresias (Fisher 2018), Cassils gazes out at us from behind the mask’s blinded eyes as spectacle and oracle.

Behold Tiresias, who was transfigured from man into woman, and carries the mystical knowledge of transformation and its beauty of becoming trapped in the staged presentation and posed performance of physical appearance that represents neither beauty nor becoming.

3.5. M. Lamar—Negro Antichrist

Figure 9. From Self to #Selfie, Installation View. Exhibition at SOMArts Cultural Center, San Francisco, CA, curated by Rudy Lemcke. Left to Right: Kia LaBeija, M. Lamar, boychild, Cassils. Photo by Rudy Lemcke.

I have known of M. Lamar’s work since their student days at the San Francisco Art Institute, a lifetime ago for both of us. A more recent solo show, NEGROGOTHIC marked Lamar’s return to SFAI in 2015.

Lamar’s Negro Antichrist is the summoning of another self. Its haunting incantation transforms the performer into an otherworldly being. Their bel canto voice is the voice of the enraged dead whose dark specter of American racism haunts this portrait of self as afro-queer-punk-diva. “Get down from that tree … beautiful negro, the beautiful negro,” Lamar sings as they rise from a grave under a tree of lynched bodies in Negro Antichrist Lamar’s performance infuses the performance with the defiance of Billy Holliday’s Strange Fruit (1945)[4], of Nina Simone’s Backlash Blues (1976)[5], with the in-your-face punch of metal punk and the supreme attitude of diva Leontyne Price (2001)[6]. As its part in the visual field of the exhibition (Figure 9), it reminds us that we cannot stray too far from our violent past. It is this history of violence that operates and organizes existentially the referential field within which we know our queer selves.

Figure 10. Kia LaBeija, Dove, digital video, 4:51 min, digital video, directed by Jacob Krupnick, 2016. Photo courtesy the artist, used with permission.

3.6. Kia LaBeija—Without Love directed by Jacob Krupnick

I first became aware of Kia LaBeija’s work in the Art, AIDS America (2015)[7] exhibition curated by Johnathan Katz and Rock Hushka, an exhibition that also included my own artwork. The show was a deeply moving life event for me as I came to know the lives of the other artists through their work. The powerful self-portraits of LaBeija on view, together with her activism around the inclusion of more people of color in the exhibition, were the elements of her practice that I wanted to include in this exhibition about queer self-representation. A spirit of going beyond her self-portraits with a concern for the just representation of others is what I love most about Kia LaBeija’s work.

In Pillar Point’s music video Dove, directed by Jacob Krupnick, Kia LaBeija frames and un-frames herself in an extended vogue performance through the streets of Bogota, Colombia. The video begins with dancer Tania Larot holding a caged dove then cuts to Kia LaBeija’s vogue performance (Figure 10). The two dancers eventually meet, and the trapped dove is freed in the video’s final sequence.

Dove carries with it the lineage of vogue performance brilliantly documented in the 1990 film Paris Is Burning (1990) that celebrates the defiance of a community ravaged by racism and later by AIDS.[8] With the creation of drag houses such as the House of LaBeija to which Kia once belonged, alternative “families” of ostracized queers, people of color, gender non-conforming and transgender youth formed new bonds and familial relations around the creation of a performance art form most notably recognized by a stylized parody of the predominantly white high fashion runway world.

The unbound joy and attitude of LaBeija’s performance speaks as a rallying call to a new generation of queer, trans, POC artists and reads for an older generation as an echo of a wounded past touched by a life-affirming future.

“Strike a pose!”

Figure 11. Awilda Rodriguez Lora, La Mujer Maravilla: INDIA$, video document, 2013–2015, Miami Performance International Festival 2015. Photograph courtesy the artist, used with permission.

3.7. Awilda Rodriguez Lora—A visual and sound journey of La Mujer Maravilla (Wonder Woman) 2013–2015

Awilda’s video is a travelogue of her journeys between her residencies in Puerto Rico and New York and the emergence of her artistic expression as a Wonder Woman. The director of a small but important performance space recommended her work to me. And although the video is a less polished piece of video art than some of the other works in the exhibition, it represents a type of performance documentation as work-in-progress, as process, as work not formatted and formed as a packaged whole but as a continuum. The video is the very stuff of the dynamic aesthetic of the exhibition. Simply put, Rodriguez Lora reproduces the scene of her identity by allowing the audience to dress and undress her (Figure 11). It brings to mind Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece (1964)[9]. But Rodriquez Lora’s constructed character moves out of passivity to perform narrative histories of colonialism, of determined normalcy, and ultimately emerges as an agent of transformation.

Figure 12. Evan Ifekoya, My Tender Touch Screen, digital, 4 min. Installation view, 2014. Photo by Rudy Lemcke.

3.8. Evan Ifekoya—My Tender Touch Screen

Evan Ifekoya came to my attention on a blog post somewhere about gender queer artists that were making a big splash on the Internet. I clicked on the link to My Tender Touch Screen and after watching it, immediately reached out to Evan to see if we could screen it in the #Selfie show.

Evan Ifekoya’s My Tender Touch Screen (Figure 12), is a parody of music videos with its green screen, canned transitions and over saturated colors. It takes us quickly into our culture of nowness—with an Instagram flash of life moments, sunsets, emojis and #Selfies. But its humorous lampoon of screen culture brings with it the serious question of the exhibition, “Who is smiling back at me from my smart phone?”

Near the beginning of the video a close-up of the artist’s mouth repeatedly asks: “Any new followers? Any new likes? Any new requests? Am I trending? Am I Now? My name’s a hashtag on my selfie, #wow!” Its repetition is humorous and troubling. It brings to mind the unsettling monologue of Samuel Beckett’s 1972 play, Not I, in which a single babbling mouth spotlighted on a nearly empty stage cries: “…out…into this world…this world…tiny little thing…before its time…in a godfor…what?…girl?…yes…tiny little girl…into this …out into this…before her time…godforsaken hole called …no matter…”.[10]

Are these two monologues similar tales of alienated outcasts, one pre and one post smart phone? One is seemingly trapped in the space of traumatic abjection, the other floating in the space of a million others. Yes and No. The horror of the abject self lies in the inability to be recognized or recognize self as self, existing in a space foreign to the field of signification. Unlike Beckett’s Not I self, for Ifekoya’s there is a fundamental care and intention at work in the seeming frivolity of the voice over. Even in its self-centeredness it points outward in search of affirmation—to a wholeness that is always bound in a relationship to a totality beyond itself. The close-up shot of Ifekoya’s mouth soon cuts back into an array of full-body shots. Ifekoya’s self is then always reflected and reproduced as #Selfie, a self that is already at work in a network of other selves to which and from which it can be seen and known. Ifekoya’s intention, even at a distance on screen, is to be touched. A self of queer liberation in all of its dynamic multiplicity that is open to the world—connected.

“My name’s a hashtag on my selfie, #wow!” (Figure 13)

Figure 13. Evan Ifekoya, My Tender Touch Screen, digital, 4 min. Graphic courtesy of the artist 2014, used with permission.

- Conclusion

From Self to #Selfie (2017) is organized as a response to the first visual art exhibition of the Queer Cultural Center (QCC). FACE: Queerness in Self Portraiture (1998) was a statement about the LGBTQ community of artists in the Bay Area in the late nineties and the launching of QCC as one of San Francisco’s officially recognized and funded community cultural centers. Its arrival on the cultural landscape was a hard fought battle engaged in by a hand full of QCC’s founding members (QCC 1998). The opening of the show was a celebration of our presence and visibility. Twenty years later, any singular queer art exhibition of self-portraits seems inadequate in representing the diversity and complexity of self-expression in our community. Rather than focusing on portraiture as such, the idea for From Self to #Selfie is to create a sense of queerness as an expression or sensation of the dynamic potential of “self” made available in our current political, technological, and historical moment. The exhibition creates an immersive environment that features nine video artworks, each beautifully complex and idiosyncratic. Supporting these projections in the corners of the gallery are four video loops of 100 #Selfies of Bay Area artists. The intension is to shift our thinking about ourselves as queer subjects. A turning from a righteous claim to presence and visibility that marked the FACE exhibition to a more nuanced enigmatic unfolding of self as desiring subjects within a complex system of relations that are bound to one another in a shared existence. The dynamics of the exhibition affords an experience of self as a potentiality—where the self manifests as both figure and background, as both fixed and unstable. The sometimes frivolous, sometimes studied individual #Selfies that circulate at the supporting corners of the space are both signified and signifiers, audience and actors in an extended network of meaning. They are ecstatic selves. They signal an elated, enraptured, entranced, euphoric, exhilarated, giddy, rapturous moment of the imminent presence of their becoming.

Footnotes

[1] Diego Velazquez, Las Meninas, 1656, Oil on Canvas, Museo del Prado. Available online: https://www.museodelprado.es/en/the-collection/art-work/las-meninas/9fdc7800-9ade-48b0-ab8b-edee94ea877f (accessed on 16 November 2019).

[2] Cage, John. 1952. 4’33. Performance by Musical Instrument Museum, curated by Daniel C. Piper, recorded 22 October 2012. See “4’33 by John Cage,” YouTube video, 08:16 min, posted by “MIMphx,” October 22, 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mr9YnBaZBgc (accessed on 16 November 2019).

[3] David Weisbart, “You’re Tearing Me Apart Scene (2/10),” Rebel Without a Cause, directed by Nicholas Ray (1955; Burbank, CA: Warner). See “Rebel Without a Cause (1955)—You’re Tearing Me Apart Scene (2/10) | Movieclips,” YouTube video, 02:08 min, posted by “Movieclips,” January 30, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UBOcWFBBB04 (accessed on 16 November 2019).

[4] Billie Holiday, Strange Fruit. Clef Records, 1954. See “Billie Holiday – “Strange Fruit” Live 1959 [Reelin’ In The Years Archives],” YouTube video, 03:18 min, posted by “ReelinInTheYears66,” February 22, 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-DGY9HvChXk (accessed on 16 November 2019).

[5] See “Nina Simone Live At Montreux 1976—Backlash Blues,” YouTube video, 06:46 min, posted by “bernardobarcellos,” October 11, 2008, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SxX6pYrvGy4 (accessed on 16 November 2019).

[6] See “LEONTYNE PRICE — 2001 — GOD BLESS AMERICA,” YouTube video, 03:40 min, posted by “Jor Taga,”, June 15, 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2jJjsQGUU-8&list=RDjovQPbJXTEU&index=9 (accessed on 16 November 2019).

[7] Art AIDS America, October 3, 2015 – January 10, 2016. Organized by Tacoma Art Museum in partnership with The Bronx Museum of the Arts, co-curated by Jonathan David Katz and Rock Hushka. Available online: https://www.tacomaartmuseum.org/exhibit/aaa/ (accessed on 16 November 2019).

[8] “PARIS IS BURNING | Official HD Restoration Trailer (2019) | LGBTQ DOCUMENTARY | Film Threat Trailers,”. YouTube video, 01:39 min, posted by “Film Threat,” May 17, 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o47CwiJLpes (accessed on 16 November 2019).

[9] Yoko Ono Performing (Samuel Becket 2019t. See “Not I,” YouTube video, 07:28 min, posted by “Fernando Silva,” December 7, 2006, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l8C4HL2LyWU (accessed on 16 November 2019).

[10] Samuel Beckett, Not I, 1972. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l8C4HL2LyWU 00:00:10 (accessed on 17 July 2020).

References

(Lemcke 1998) Lemcke, Rudy. 1998. FACE: Queer Self-Portraiture. Exhibition Catalog. San Francisco: Queer Cultural Center.

(Shimono 1993) Shimono, Sab. 1993. Suture. Directed by Scott McGehee and David Siegel, Produced by Scott McGehee and David Siegel.

(Black 2019) Black, Athena. Riding the Wet, Wet Wave: An Interview with A.K. Burns and A.L. Steiner on Community Action Center. NOMOREPOTLUCKS 2012, 19. Available online: http://nomorepotlucks.org/site/interview-with-ak-burns-and-al-steiner-on-community-action-centre/ (accessed on 17 July 2020).

(Fisher 2018) Fisher, Martini. 2018. Tiresias, Blinded by the Gods and Blessed with Second Sight, 2018. Ancient Origins: Reconstructing the Story of Humanity’s Past. Available online: https://www.ancient-origins.net/history/tiresias-0011095 (accessed on 17 July 2020).

Artists

100 Selfies (Figure 2 in detail)

Top Row: Celeste Chan and Maxine Hong Kingston, Annah Anti Palindrome.

Ann Aptaker, Annie M. Sprinkle andm Beth Stephens, Jerome Caja, Evie Leder, Gary Freeman and Nick Macierz, Beth Pickens, Gabrielle Le Roux, Rudy Lemcke.

Row Two: Dr. Jordy Tackitt-Jones, Jamee Crusan, Jason Hanasik, Kim Anno, Lenore Chinn, Lorenzo DeAlmeida, Maureen Burdock, Nicki Green, Raquel Gutiérrez, Rotimi Agbabiaka.

Row Three: Aron Kantor, Alex Hernandez, Cooper Lee Bombardier, Stathis Gerostathopoulos, Sam Cortez, Zeph Fishlyn, Pamela Peniston, E.G. Crichton, Dorian Katz, Debra Walker, Audaciously Speaking.

Row Four: Emily Holmes, Amanda Simons, KB Boyce, Kevin Seaman, Sean Dorsey, Shawna Virago, Emily Park, Dr Eagle Bear, Favianna Rodriguez, Ramekon O’Arwisters.

Bottom Row: Việt Lê, Virgie Tovar, Dorothy Santos, Amy Sueyoshi and Tina Takemoto, Amy Cancelmo, Fallon Young, Indira Allegra, Natalia Vigil, Katie Gilmartin, Amy Wilson.

boychild (Figure 1, 6, and 9)

DLIHCYOB, Dir. 2012. Moore, Mitch. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lI5lfTIyGgw (accessed November 16, 2019).

Cassils (Figure 1, 8, and 9)

Cassils. Available online: https://www.cassils.net/cassils-artwork-oeuvre (accessed on 16 November 2019).

Cassils. Hard Times. Franklin Furnace. 2010. Available online: https://vimeo.com/38263782 (accessed on 16 November 2019).

Crichton, E.G. (Figure 3)

Crichton, E.G. Available online: https://egcrichton.sites.ucsc.edu/ (accessed on 16 November 2019).

Ifekoya, Evan (Figure 1, 12, and 13)

Ifekoya, Evan. Available online: http://evanifekoya.com/ (accessed on 16 November 2019).

Ifekoya, Evan. My Tender Touch Screen (not available for preview).

LaBeija, Kia (Figure 4, 9, and 10)

LaBeija, Kia. Available online: https://visualaids.org/artists/kia-labeija (accessed on 16 November 2019).

LaBeija, Kia, Dir Dove, and Jacob Krupnick. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BU6dAAfg-qk (accessed on 16 November 2019).

Lamar, M. (Figure 1 and 9)

Lamar, M. Available online: http://www.mlamar.com/ (accessed on 16 November 2019).

Lamar, M. Negro Antichrist. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iqPpvQ6TQkc (accessed on 16 November 2019).

Rodriguez Lora, Awilda (Figure 11)

Lora, Awilda Rodriguez. Available online: http://laperformera.org/ (accessed on 16 November 2019).

Lora, Awilda Rodriguez, and La Mujer Maravilla. (not available for preview).

Steiner, A.L. (Figure 7)

Steiner, A.L. Available online: https://www.hellomynameissteiner.com/ (accessed on 16 November 2019).

Steiner, A.L. Swift Path To Glory (excerpt), 2003/2007. Available online: https://vimeo.com/25616002 (accessed on 16 November 2019).

Takemoto, Tina (Figure 5)

Takemoto, Tina. Available online: http://www.ttakemoto.com/index.html (accessed on 16 November 2019).

Tina Takemoto, Semiotics of Sab (excerpt), 2016. Available online: https://www.cfmdc.org/film/4544 (accessed on 16 November 2019).