The Search For Life in Distant Galaxies

On Sunday mornings he played chess at the public tables on Market Street. His favorite partner was an elderly man that he affectionately nicknamed Magister Ludi. Magister Ludi had been living in the Tenderloin since the late 50’s—since the time he had been discharged from the navy. He had been a ships navigator and had an encyclopedic knowledge of the stars. They would talk for hours about distant galaxies, time travel, extra-terrestrial life, the origin of light and the inevitable collapse of our solar system. How Magister Ludi became homeless was a mystery that was never discussed, it was just a constant, a given, an unfortunate fact of life. Unlike other players at the public boards who kept their friendships confined to the game, over time, Ed had developed a genuine love for Magister Ludi, and it troubled him that there was nothing he could do to help his friend. But this was the dimension that Magister Ludi chose to live in and the chessboard was a freely chosen portal to the alleyways and dead end streets where he lived and traveled through space and time. Even though Ed understood on many levels what Magister Ludi meant when he described the astral phenomenology of his everyday life, he could not help but feel sorrow as he observed his friend’s real poverty and increasing frailty and fearfulness.

The last time he saw Magister Ludi he was standing at the Powell Street Bart station near the cable car turn-around handing out photo copies of a poem about the coming galactic cataclysm, the end of life as we have known it—an event triggered by an unforeseen, unstoppable extra-terrestrial anomaly.

The poem was one continuous stream of thoughts that spiraled out to the edges of the page and then on to the other side where it spiraled inward until the words disappeared into its center.

Ed Marker knew that he would never see his friend again; that the portal was closing, and that there was truly nothing that he could do to change things. His chess partner was unreachable and between worlds now.

Magister Ludi had been the only person, since the death of his friend James, who understood the curious mechanics of the Tenderloin as Ed Marker did. And now, he too felt frail and fearful. He feared that this knowledge would be lost. He feared the future. He tried to dismiss this feeling, block it out, trying to erase it by focusing on his unfinished project but the thought of the empty boxes that awaited him at home only made things worse. He felt more and more like a stranger walking the streets of a city that he had charted so intimately over the years. These very streets were now becoming unfamiliar.

Walking up Eddy Street he felt the dizziness of time as his own portal to this place was closing in on him. He tried to remind himself that he might be nearing a collapsing star or actually entering a wormhole and to not be afraid. This was all in the notebooks, all foreshadowed in the data, part of the forces of cosmic change that he had been recording for all of these years—part of the expansion of the universe. He continued to walk the busy streets back to his apartment, avoiding the chessboards and any other hazardous warps in space-time.

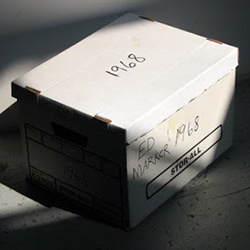

He would eventually put the poem in an envelope, with “Magister Ludi” written on its front, inside his old copy of Herman Hesse’s Siddhartha, next to a letter addressed to his friend James; and place the book in the box marked 1968.

He hoped that Magister Ludi would have a better incarnation the next time around.